Monday, August 25 at 1:45pm

Me, Myself & Irene

Directed by Bobby and Peter Farrelly (U.S. 2000) 116 min. 35MM. With Jim Carrey, Renée Zellweger.

Directors excelling in the traditions of both gross-out and “brothers making comedy” films, the Farrellys produced such 90’s hits as Dumb and Dumber (1994) and There’s Something About Mary (1998). With “scripts [that] would always have one foot planted firmly in the sewer” (The New York Times), the brothers revel in rude sounds and also in characters who are losers, often losers in love. Needless to say, some of the humor dates – the awkward feeling that maybe we shouldn’t be laughing raises interesting questions about just how much the morals of popular culture have (or haven’t) changed in the last three decades. In Me, Myself & Irene, Jim Carrey stars as a Rhode Island state trooper with Multiple Personality Disorder. When he fails to take his medication, his personalities fall in love with Renée Zellweger’s Irene…

Monday, September 1 at 1:45pm

Flirt

Directed by Hal Hartley (U.S. 1996) 85 min. 35MM. With Parker Posey, Bill Sage, Dwight Ewell, Miho Nikaido, Martin Donovan.

Per the Criterion Channel’s retrospective two years ago, Hal Hartley is a true independent, boasting one of the most idiosyncratic bodies of work in all of contemporary cinema. First emerging in the late 1980s and early ’90s with a fully formed sensibility on display in the barbed romantic comedies The Unbelievable Truth and Trust, he quickly became one of the most acclaimed voices on the indie circuit. But while many of his peers moved toward the mainstream, Hartley continued to cultivate his own decidedly personal methods. Marked by their deadpan wit, formal rigor, underground-rock soundtracks (featuring Yo La Tengo and Sonic Youth as well as the director’s own compositions) and offbeat performances (from rising stars such as Adrienne Shelly, Parker Posey, Edie Falco, Martin Donovan, and Elina Löwensohn), his films are unmistakably his, preternaturally attuned to language, behavior, and the dynamics between his vividly drawn characters. Flirt is a simple story of love and loss told three times in three different cities: New York, Berlin, and Tokyo, repeating the same situations and dialogue but with subtle shifts of emphasis. Print courtesy of the Academy Film Archive.

Monday, September 15 at 1:45pm

The Circus

Directed by Charlie Chaplin (U.S. 1928) 72 min. 35MM. With Charlie Chaplin, Merna Kennedy.

When we first meet Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp in this comic gem, he’s in typical straits: broke, hungry, destined to fall in love, and just as sure to lose the girl. Mistaken for a pickpocket and pursued by a peace officer into a circus tent, the Tramp becomes a star when delighted patrons think his escape from John Law is an act. At the first ever Academy Awards ceremony, Chaplin was honored with a special statuette for “versatility and genius in writing, acting, directing, and producing The Circus.” And, it went without saying, for again bringing laughter to packed movie palaces across America. One of the funniest comedies of all time, The Circus is also “the most personal and self-revelatory film ever made by a major director” (MOMA).

Monday, September 22 at 1:45pm

The Trouble with Harry

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock (U.S. 1955) 99 min. 35MM. With Edmund Gwenn, John Forsythe, Mildred Natwick.

In the midst of his dark Fifties’ masterworks Hitchcock found a moment of oddly whimsical and bucolic repose in his second comedy, an affectionate valentine to the small town America that had so captured his imagination earlier on in Shadow of a Doubt. A disastrous failure at the box office, John Michael Hayes’ adaptation of an eponymous play about village folk strangely unperturbed by the appearance of a corpse they each try calmly but unsuccessfully to get rid of, The Trouble With Harry has since been recognized as one of Hitchcock’s most surrealist films. Hitchcock’s only film set in New England, The Trouble With Harry made dramatic use of its Vermont location and autumnal season, with the fall foliage gorgeously showcased in radiant Technicolor (Harvard Film Archive notes).

Monday, September 29 at 1:45pm

The Great Moment

Directed by Preston Sturges (U.S. 1944) 83 min. 35MM. With Joel McCrea, Betty Field, Franklin Pangborn, Porter Hall, Harry Carey.

Legendary filmmaker Preston Sturges, the writer/director of The Great McGinty, Christmas in July, The Lady Eve and Sullivan’s Travels, turns to a more serious subject matter focusing on one of the great medical discoveries in modern history. Joel McCrea, as W.T.G. Morton, the 19th-century dentist who discovered anesthesia, plays the straight man to the Sturges stock company in a bizarre combination of slapstick and stark drama — told in complicated flashback style that ultimately sets up the electrifying final moment. Despite being shelved and tampered with by befuddled studio execs, it’s still a rare personal statement. (adapted from Film Forum notes). Playing with Mark LaPore’s The Sleepers (1989, 16mm, 16 min.), in which “time and space contradict, then collapse to suggest a new third world city; a city of the imagination, where rural Sudan, China and Manhattan exist simultaneously” (ML).

Monday, October 6 at 1:45pm

A Couch in New York

Directed by Chantal Akerman (Belgium/France/Germany 1998) 108 min. DCP. With Juliette Binoche, William Hurt, Barbara Garrick, Paul Guilfoyle, Richard Jenkins. In English and French; English subtitles

Chantal Akerman’s sendup of psychoanalysis imagines the talking cure as an act of seduction. Swapping homes means swapping lives. In this Lubitschian romantic comedy of mistaken identities, misunderstandings, inverted roles, and motherly love, the free-spirited, straight-talking Béatrice (Binoche) trades her messy Parisian apartment with Henry (Hurt), a buttoned-up New York shrink with a pristinely curated Fifth Avenue penthouse, a golden retriever, and a fiancée. Henry discovers on his return to New York that Béatrice is conducting therapy sessions with his neurotic patients. Intrigued, he pretends to be one of them and soon finds himself on the proverbial couch. As the transference and countertransference inevitably take hold, so too does their love (adapted from Museum of Modern Art notes).

Monday, October 27 at 1:45pm

Terrifier 3

Directed by Damien Leone (U.S. 2024) 125 min. DCP. With David Howard Thornton, Daniel Roebuck, Lauren LaVera, Elliott Fullam, Samantha Scaffidi, Margaret Anne Florence.

After surviving Art the Clown’s Halloween massacre, Sienna and her brother struggle to rebuild their shattered lives. As the holiday season approaches, they try to embrace the Christmas spirit and leave the horrors of the past behind. However, just when they think they’re safe, Art returns, determined to turn their holiday cheer into a new nightmare. You better not shout, you better not cry. Per the TERROR-FI Film Festival, “slasher fans are in for a treat on Opening Night. If you thought TERRIFIER 2 was delightfully depraved… TERRIFIER 3 takes the diabolical franchise to a whole new level.”

Monday, November 3rd at 1:45pm

Détective

Directed by Jean-Luc Godard (France/Switzerland 1985) 95 min. With Claude Brasseur, Nathalie Baye, Johnny Halliday, Jean-Pierre Léaud. French with English subtitles.

A mainstream genre picture sacrificed on the altar of the late, great Jean-Luc Godard, Détective is a cunning, comic deconstruction of the film noir. Its convoluted yarn, a noir forte, crams a handful of gangster-movie archetypes—sleuths, dames, mafia debtors, and debt collectors—into a Parisian hotel and lets their unspooling plotlines entangle one another. The film was a commission job: producer Alain Sarde had a script and star attached (Baye); Godard was short of cash to finish Hail Mary. The puckish fun of Détective comes from how the director and his collaborator Anne-Marie Miéville inside-out the assignment, making window dressing out of the story while reflexively calling back to Godard’s crime pictures of the ’60s (e.g. Band of Outsiders). Jean-Pierre Léaud is memorable as a manic gumshoe stumped by a prince’s murder. A teenage Julie Delpy appears in a minor role (adapted from Vancouver Cinematheque notes).

“A mini-masterpiece … Built on the charisma of its stars and on memories of the great thrillers of the ’40s [and] held together by Godard’s romantic pessimism, curiosity, and sense of humor.”

–Tony Rayns, Time Out

Monday, November 10th at 1:45pm

Othello

Directed by Orson Welles (Morocco/France/UK/U.S. 1951) 91 min. DCP. With Orson Welles, Suzanne Cloutier, Micheàl MacLiammoir.

Gloriously cinematic despite its tiny budget, Orson Welles’s Othello is a testament to the filmmaker’s stubborn willingness to pursue his vision to the ends of the earth. Unmatched in his passionate identification with Shakespeare’s imagination, Welles brings his inventive visual approach to this enduring tragedy of jealousy, bigotry, and rage, and also gives a towering performance as the Moor of Venice, alongside Suzanne Cloutier as the innocent Desdemona, and Micheál MacLiammóir as the scheming Iago. Shot over the course of three years in Italy and Morocco and plagued by many logistical problems, this fiercely independent film joins Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight in making the case for Welles as the cinema’s most audacious interpreter of the Bard.

“It may well be the greatest Shakespeare—a brooding expressionist dream made in eerie Moorish locations over nearly three years, yet held together by a remarkably cohesive style and atmosphere.” – Jonathan Rosenbaum, Chicago Reader

Monday, November 17th at 1:45pm

Journeys From Berlin/1971 – Restoration!

Directed by Yvonne Rainer (U.S. 1979) 125 min. DCP.

A pioneering figure of the avant garde movement, Yvonne Rainer’s artistic career spans over five decades across both dance and film. Her fourth feature, inspired by her experiences living in West Berlin in 1976 and ’77, when the activities of right-wing terrorists were at their height, offers an audacious, collage-like meditation on state power, repression, violence, and revolution. Vaulting between aerial images of British landscapes, intertitles, fragments of Rainer’s teenage diary, and one unseen couple’s debate (voiced by Amy Taubin and Vito Acconci) over the demise of the RAF, the film is illuminated by a lead performance from the late art and film critic Annette Michelson as a patient undergoing psychoanalysis, whose every gesture was choreographed elaborately by Rainer over a nine-month period.

“Without a doubt the most ambitious, most risk-taking work of Rainer’s cinematic career.”—B. Ruby Rich

Monday, December 1 at 1:45pm

The Clock

Directed by Vincente Minnelli (U.S. 1945) 90 min. 35MM. With Judy Garland, Robert Walker, James Gleason.

The Clock marks Judy Garland’s first non-musical star vehicle and – on the strength of his great success with Garland on Meet Me in St. Louis, MGM put Minnelli in charge of the picture. He responded immediately to the urgency and vitality of the story’s time and place: New York City during World War II. On a two-day pass, Robert Walker’s gangly soldier clings to Garland’s sympathetic secretary for a whirlwind courtship in the hours before he ships overseas, only to lose her in the city’s rush. The sounds of the city itself serenade the lovers—tug boat horns and subway rails set the mood in Riverside Park—while Minnelli never flinches from the wartime backdrop that underscores the romance with desperate uncertainty. The Clock demonstrates Minnelli’s early ability to give the affective lives of his protagonists vivid urgency onscreen (adapted from Harvard Film Archive notes).

Monday, December 8 at 1:45pm

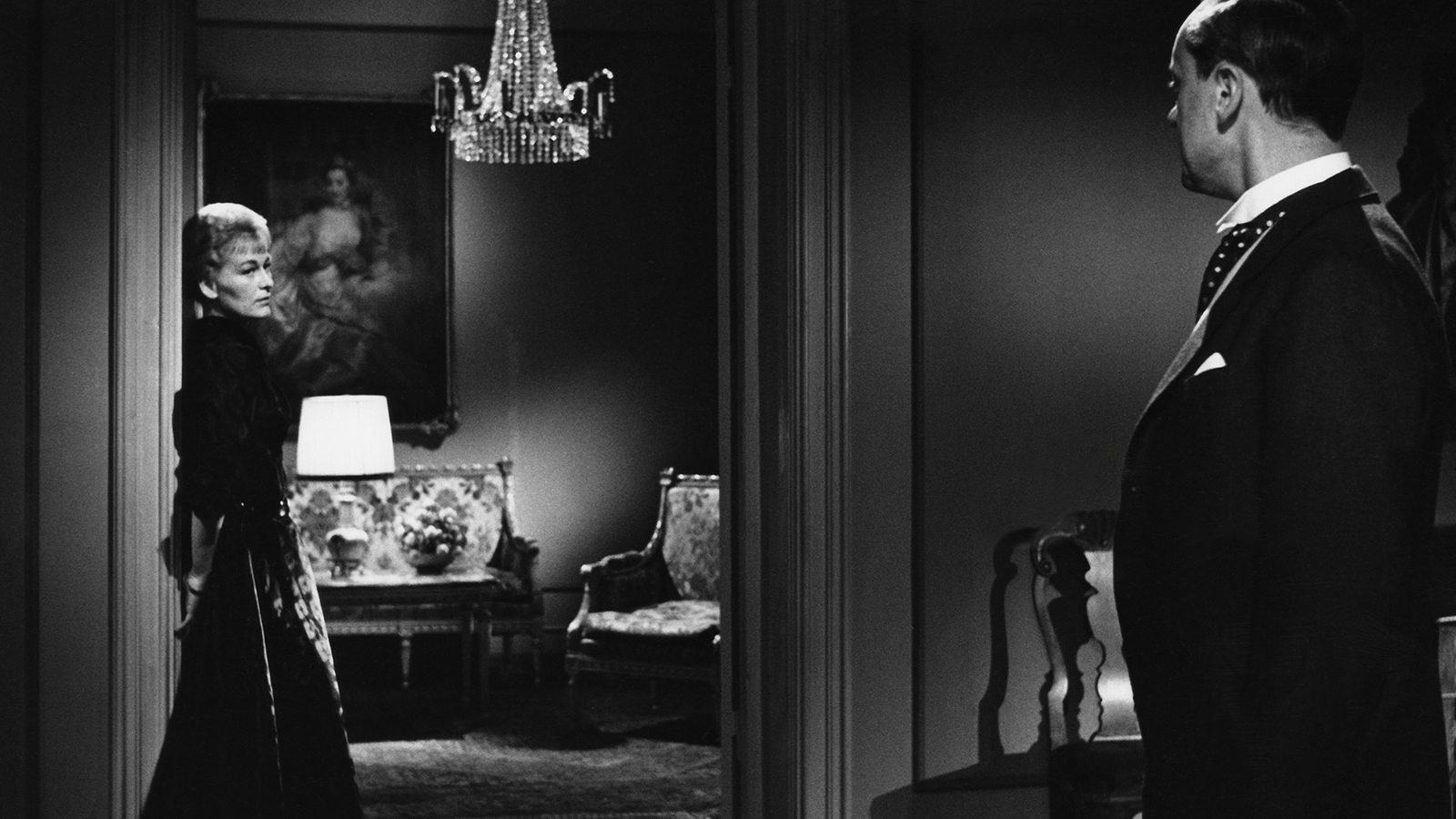

Gertrud

Directed by Carl Theodor Dryer (Denmark 1964) 119 min. 35MM. With Nina Pens Rode, Bendt Rothe, Ebbe Rode, Baard Owe. Danish with English subtitles.

Carl Dreyer’s last film neatly crowns his career: a meditation on tragedy, individual will and the refusal to compromise. A woman leaves her unfulfilling marriage and embarks on a search for ideal love—but neither a passionate affair with a younger man nor the return of an old romance can provide the answer she seeks. Always the stylistic innovator, Dreyer employs long takes and theatrical staging to concentrate on Nina Pens Rode’s sublime portrayal of the proud and courageous Gertrud.

“There is no other movie like Gertrud. It exists in its own bright, one-entry category, idiosyncratic, serenely stubborn, and sublime. When it opened in 1964, Carl Theodor Dreyer’s last film, one of his greatest, generated a scandal from which it has never completely divested itself.”— Phillip Lopate, The Criterion Current